Right from creating a dedicated financial institution in the late 1980s to rolling out incentive schemes in the early 1990s, the govt has provided several avenues for clean energy financing in India. This apart, alternative funding avenues are created for the sector in the form of mechanisms like the National Clean Energy and Environment Fund (NCEEF) and instruments like green bonds and renewable energy certificates. Below we discuss some of the operational sources and schemes of financing in the sector and the challenges faced by them.

Avenues of clean energy financing and incentive schemes in India

1. Public financing

The Centre created a dedicated financial institution called the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency Limited (IREDA) under MNRE in 1987 to provide financial aid such as soft loans, counter guarantees, and securitization of future cash flows to RE projects in India. However, as per a report by the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), 2018, IREDA loans reportedly suffer a delay in sanctioning loans.

Apart from IREDA, state-run organizations like the Power Finance Corporation (PFC), Rural Electrification Corporation (REC), and National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development (NABARD) provide finance to the RE sector.

(i) Bank Priority Sector Lending (PSL)

In 2015, RBI has included RE financing under the ambit of PSL, which is aimed at boosting employability, building basic infrastructure, and strengthening the competitiveness of the economy. The central bank has kept the loan ceiling of INR 30 crores per borrower for RE projects. However, the ADBI report pointed out that the financing flow to RE under PSL has not been turning out as expected. One reason for the shortfall is the inclusion of RE under the broader umbrella of energy causing a flow of credit to non-RE sectors.

(ii) Green Banks

Green Banks are conceptualized as a tool to accelerate clean energy financing. The first green banking initiative was undertaken by IREDA in 2016 to mobilize private funds to meet green energy targets. However, the idea has not yet taken off in India as it did abroad in countries like Japan, Australia, Switzerland, and the UK with a goal to facilitate the financing of clean energy projects at a cheaper rate. This could be attributed to the lack of mechanisms to recognize such institutions in India.

2. Green bonds

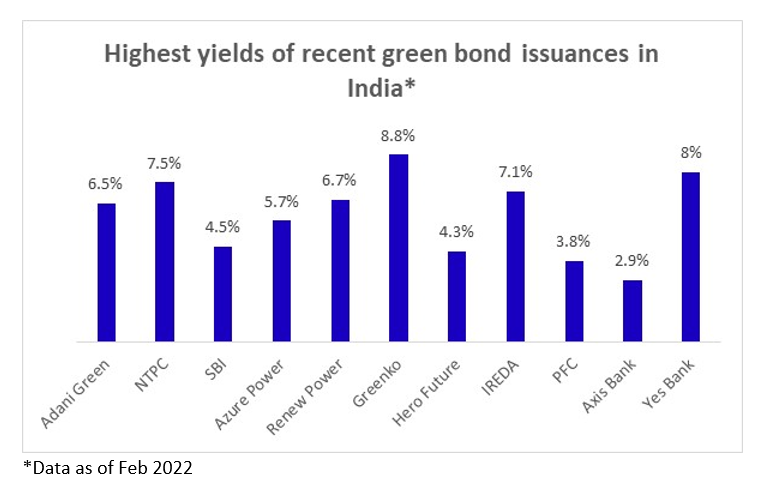

Funds raised via Green or Masala bonds are invested in green or RE projects. The tenure of green bonds in India ranges between 18 months and 30 months and they are issued for a period of up to 10 years.

India is the second country after China to have regularity guidelines formulated by SEBI for green bond issuances. They can be issued by the govt, multilateral organisations (such as ADB, the World Bank, etc), financial institutions, and corporates. They are increasingly being issued in India (listed either/both domestically and internationally). For example, SBI, India’s largest public sector lender, has launched dual listed green bonds worth US$650 million on the India International Exchange (India INX) and Luxembourg Stock Exchange. The size of total green bond issuances in India stood at ~US$7 billion in 2021. However, the issue size comprises less than 1% of the domestic bond market.

Despite creating a conducive environment, green bond issuances are yet to be a success in India because their acceptance largely depends on the risk perception of the investors. The riskiness of these bonds is similar to other bonds. They are required to be rated to attract institutional financing. The perceived risk of investment in such bonds becomes higher as some investors fear funds garnered via these bonds may not be utilized for the purpose for which they are issued. Secondly, there is an inclination of investors toward higher-rated issuers creating an asymmetry in the market.

3. Incentive schemes

Public financing in the sector also goes as support funding to incentivize the flow of private capital into the sector and tends to work as an enabling framework with a perception that the private investors have the potential to fund clean energy projects. Some of the incentive schemes rolled out for the RE sector include

- Accelerated Depreciation: The AD scheme, introduced in 2009, incentivize investors by relaxing their tax liability on the investment. It allows depreciation of investment in assets like a solar power plant at a much higher rate than general fixed assets so that tax benefits can be claimed on the value depreciated in a given year. The scheme was withdrawn in 2012 and reinstated in 2014.

- Generation-based incentive: The GBI scheme offers an incentive per kWh of energy generation in solar and wind projects. The primary intention of this scheme is to promote renewable power generation rather than only setting up RE projects. This scheme was later withdrawn mostly for utility-scale projects due to the fast growth of the RE market that resulted in near parity of RE tariffs with thermal power tariffs.

- Viability Gap Funding: VGF is a type of smart incentive scheme to finance economically justifiable infrastructural projects. It is provided as a one-time grant by the govt to make projects commercially viable and has been used by the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) to promote solar energy.

Apart from these incentive schemes, policy instruments that exist in India to push India’s RE sector include renewable portfolio obligations (RPO), renewable energy certificates (REC), and feed in-tariff (FiT) schemes.

4. Foreign equity

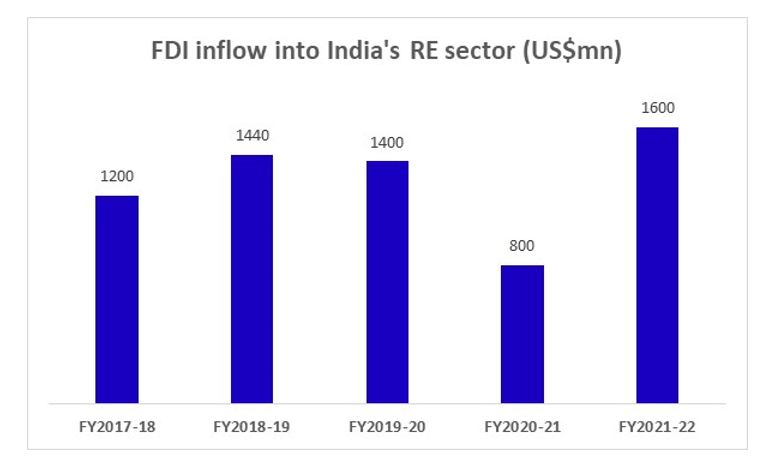

Globally, there is strong momentum in capital flow to the energy sector away from coal and coal-fired power generation in the last few years. Over the 12 years, the cumulative FDI inflow to India’s RE sector stood at ~US$12bn. Currently, 100% FDI is allowed in the RE sector under the automatic route that needs no prior approvals. Here’s how the FDI flow took place in the last five years —

The steady increase in FDI inflow, except in the year of Covid’s first wave, is driven by growing commitments to meet clean energy targets under the Paris agreement and an increasing pool of Impact Investors, who are keen on aligning their investment goals to UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. However, India is yet to attract a larger flow of foreign capital to clean energy as the domestic flow still dominates about 80% of the overall finance flows.

Lt Col Monish Ahuja, Chairman & MD of Mumbai-based Punjab Renewable Energy Systems, a provider of bioenergy and biomass solutions, expects India to become a sweet spot for global investments in the RE space. However, he believes, achieving the 2030 RE targets could be a tough ask as the investment hurdle rates required are very high unless concerted efforts are made to create a more friendly investment environment in order to access the vast pool of global capital towards sustainable ESG compliant RE businesses, including Biomass-Bioenergy, Green Hydrogen, et al.

Ahuja further added, “smaller players need to tie up and align themselves with the strategies of larger global players interested to invest in India. This will enable them to be backed by corporate guarantees / structured finance of the large balance sheet from these larger global players. Secondly, smaller players have to collaborate and come together under government programs where they can increase their bargaining power on a collective basis. Industry bodies like the Confederation of Biomass Energy Industry of India and CLEAN, a non-profit organization committed to supporting, unifying, and growing clean energy enterprises, are diligently working towards making capital accessible to the stakeholders.”

Role of Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs)

As per a study by the International Finance Corporation, India would need US$450bn in financing to meet its clean energy targets by 2030. Assuming a debt-equity split of 70-30, this means ~US$315bn has to come from the debt market. Accumulating financing of such an enormous size could be a daunting task unless new investor classes are tapped in and capital in existing projects is recycled.

However, small and medium RE project developers do not get the right access to the bond market due to the skewness of the market appetite towards G-sec and higher-rated corporate bond issuers, as discussed in the section ‘Asymmetry in debt financing’ in Part I. This creates a barrier to clean energy financing, particularly in the short to medium term. In such a scenario, AIFs fit in, not only because it provides short-medium term access to the capital market, but also due to the fact that they can

- Invest in start-ups or unlisted securities and adopt complex trading/leveraging strategies unlike other investment vehicles like mutual funds.

- Help crowding in many institutional investors for a single project due to diversification limits set by SEBI (Cat I and Cat II AIFs are not permitted to invest more than 25% of their funds in a single investee firm while, for Cat III, the limit is 10%).

- Enhance the credit rating of bond issuance by using structured finance, where the AIF sponsor could provide a partial credit guarantee using a subordination/waterfall structure and customized periodic cashflows.

- Enable private credit towards financing segments of the market such as Commercial & Industrial RE, hybrid technologies, EV network financing, etc where banks aren’t highly active yet.

- Finance standalone mid-sized projects without relying on sponsor support.

This way AIFs can enable RE developers to reduce their cost of capital and help them repay loans taken from banks/NBFCs using the proceeds from bond issuances. On the other hand, investors are assured of coupon payments as they are backed by cash flows from stable and operational projects.

The emergence of more and more AIFs in the clean energy space would increase the confidence of investors in the sector by helping them undertake calculated risks, invest for impact, and giving exposure to complex and new clean energy tech. On the other hand, it will help RE entities, which are so far reliant on few lenders like IREDA, REC and PSU banks, achieve diversification in the borrowing mix.

Disclaimer:

The views provided in this blog are the personal views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Vivriti. This article is intended for general information only and does not constitute any legal or other advice or suggestion. This article does not constitute an offer or an invitation to make an offer for any investment.